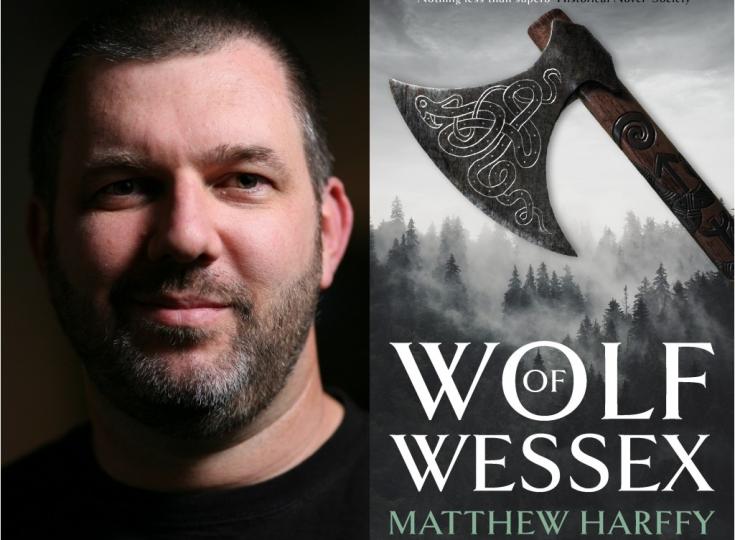

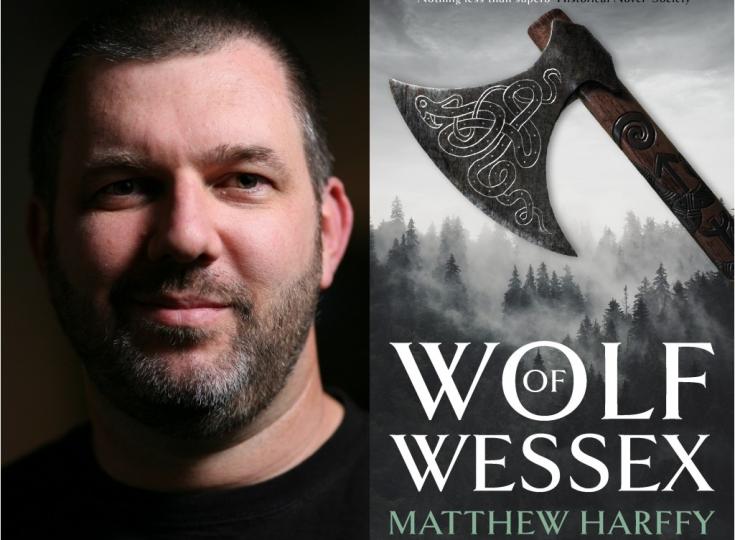

In my current work in progress (working title, Wolf of Wessex, to be released in the second half of 2019), the main character, Dunston ‘The Bold’, wields an extraordinary axe. My first inclination when writing the book was that I would like it to be a double-headed, fantasy style axe like that wielded by David Gemmell’s Druss, or Robert E. Howard's Conan.

|

| Conan by Earl Norem |

Alas, a little research told me that double-headed axes of that type did not exist in Viking Age Britain. And so I was stuck with the single-bladed variety, but there was no reason why it could not be special. And so I began to investigate unusual axes from the period and found the famous Mammen axe, which has a head where silver has been forged in intricate patterns into the iron.

|

| The Mammen axe |

Such a patterned blade appealed and then I thought of the other ways in which an axe could be made special and the obvious answer was that its haft could be carved, and being a Viking axe, it would be carved with runes of significance and possibly magical power.

In Wolf of Wessex the weapon is described as follows:

"The axe's dark iron head was swirled with intricate patterns of silver, which had been cunningly forged into the metal, and the long ash haft was carved with runes and symbols. The lower end of the shaft was tightly bound in old, worn leather.”

When I finished writing the first draft of the book, I decided that I would treat myself to an axe that I could hang on my wall. Of course the axe as described in the book did not exist and so I looked at what other options were available to me. There are replicas of the Mammen axe, but it isn't much more than a hatchet in size and so not the giant battle axe I had envisaged being hefted by my hero, Dunston.

It was about this time that I saw a post on the

Bernard Cornwell Fan Club Facebook group about an axe that the admin of the group, Chris Bailey, had customised for somebody. The axe had carving, runes and some leather wrapping. The resulting weapon looked amazing and so I reached out to Chris and asked whether he would be interested in creating something for me that approximated the axe carried by Dunston.

Chris immediately accepted the challenge, but was very modest about his abilities and in particular, was nervous about the idea of doing anything to the steel head of an axe. I thought it would be possible to etch or engrave into a darkened head, showing the bright metal beneath. Chris had never attempted anything like what I was suggesting before and was worried that it might not work or he might not be up to it. But, deciding to cross that bridge when we came to it, he accepted the commission and off we went.

The first thing we had to do was to decide on the axe that was to be used as a basis for the customization. Anyone who knows anything about Viking period axes will know there are lots of different shaped heads depending on the exact part of the centuries-long period you are dealing with.

Wolf of Wessex is set in A.D. 838 and, strictly speaking, the type of axe used by Norsemen in that period would probably be a Petersen type A – E axe head type. However, I decided that this is fiction, and I wanted a bigger head on the axe and so we continued searching until Chris found the Danish War Axe manufactured by Hanwei. Ideally, and historically, the head would be friction fitted rather than pinned, and the shape wasn’t exactly right (it was close to a type M shape, but seemed to be the wrong way up), but, despite these things and the fact that such a long hafted, large headed axe would post date the 9th century, we both liked the size and shape of the axe. What we didn’t like were the aging effects that the producers had decided to inflict upon the metal and wood.

|

| Hanwei Danish War Axe |

So, with the axe chosen, I ordered one to be delivered to Chris and we set about designing the carvings. Many messages were exchanged via Facebook messenger with sketches of runes and other shapes found in Viking age carving. We both wanted the final product to be arresting, artistic and eye-catching and, whilst not being necessarily 100% historically accurate, not knowingly anachronistic in design. But we were also cautious of making things too complex. Chris was keen to remind me that he was a novice at this and he didn't want to overstretch himself. I was appreciative of all of the time and effort he was putting in and didn't want to ask for more than was possible. In the end, I needn't have worried. I think his skills surpassed what he thought he was capable of and he produced a thing of true beauty.

For the runes I decided on using the meaning of each rune for a spell rather than having each rune signifying a letter. In that way the runes could be interpreted as an incantation something like the following:

"With the power of Odin and one-handed Tyr, let the mortal man who wields this offspring of Yew, bring speedy anguish, death, hail and destruction on his enemies."

After the design was agreed upon, Chris set about preparing the axe for work. This necessitated stripping back all of the stain on the wood and also grinding off all of the patina of ageing on the metal. This was a large job in itself, but once Chris had finished the axe was already looking better; a blank canvas for him to begin drawing the patterns we had discussed.

|

| The Hanwei axe as it arrived from the manufacturer |

|

| Close up of the blade to show the stippled ageing effect |

|

| The axe takes its first blood! |

|

| Stripped of all the ageing, ready for the real work to begin! |

For the head of the axe and the impression of the silver inlay on the Mammen axe, we had agreed that a darkened blued steel which was then engraved with a pattern down to the clean silver steel beneath might give a good effect that would at least mimic the much more complex forging of a Mammen-style axe head. And so Chris set about bluing the metal, applying several coats until it was dark enough. This engraving was the part of the process that Chris was most worried about, but it would wait until the end, after all the carving had been done, before we would see whether he was up to the task.

|

| The head after bluing applied |

Once the head was blued, Chris set about drawing on the runes and the wyrm that would encircle the wood. There was some discussion about how to reflect the scales of the serpent. In the end, after an initial sketching out of the scales, we decided on a simpler line and dot motif based on contemporary designs found on things like the Thames seax.

|

| Initial serpent scales idea |

|

| Ideas for historically accurate scale designs |

Chris then started the carving and managed to complete that in a couple of long sessions. By this point the axe was really beginning to come to life and I was starting to get excited about holding it in my hands.

Next came the stain for the wood and after a lot of discussion, we decided on almost black for the runes and snake with a dark stain for the background wood.

Finally it was time for the etching that had been worrying Chris from the beginning. We decided on having the same design on each side following a sketch made by Chris that captured the right aesthetic. Chris girded his loins and set to it, and to his surprise, he got it done the first time and the result was just as I had hoped for.

The last step was to wrap the handle and for this, Chris used approximately 30 metres of antiqued cowhide thong (more than he had originally thought to use). As with all of the stages of the creation of the axe, there was a lot of debate about the colour of the leather to use, but in the end we chose black, as it was in keeping with the dark feel of the weapon.

I think you will agree that the finished product is superb. Who knows, it may even end up on the cover of

Wolf of Wessex, if I get my way!

After Chris had completed the project, I asked him a few questions and you can read his thoughts and experiences of the whole process here:

What was the most challenging part of this process for you?

Probably the most challenging part was engraving the head, this was something I hadn’t attempted previously and it made me a little nervous I have to admit! Matthew was supportive in his encouragement, and I like the way it turned out.

Which part of the finished product are you most proud of?

That’s difficult to say; I think I like the overall effect of the finished article, and all of the separate elements combine to achieve that. I’m quite proud of the designs Matthew and I collaborated on, I think that the colours we discussed and implemented work well, the head finish and the bluing make the engraving really pop, and I am quite pleased with how the west country whipping for the grip portion came together.

Can you give a list of the tools and materials you used?

There are a few tools used in the process:

- A rotary tool (what you might know as a Dremel, but a different brand) with a long flexible pen grip shaft.

- Many and varied bits or burrs for the rotary tool, from cutters of different shapes and sizes to diamond titanium coated engraving/polishing burrs, also of varied configurations. Sanding drums and grinding bits also.

- Diamond hand files.

- An angle grinder, with discs in degrees of coarseness and a special three disc polishing set with compounds.

- A basic clamping workbench.

- Sandpapers of varying grits.

- A sharpening stone.

- HB pencils and erasers.

- Brushes of different sizes, fine grade steel wool, cotton wool and various rags/cloths.

- A pair of magnifying glasses with varying lense strengths and an LED light (essential for the small detail work).

- A pair of surgical steel cutters which are apparently designed for ingrowing toenails but work very well for trimming leather wrapping; adapting stuff to a different purpose than intended is always great.

- A half dozen elastoplasts, for when she bit me.

Materials used were:

- Varnish stripper, Rustins Strypit

- Polishing comounds, Dronco.

- Black special effects wax, Liberon.

- An acetone clear matt protective coating, Rust-Oleum.

- A cold blueing solution, Birchwood Casey Super Blue.

- A lubricant/water repellent, GT-85.

- A stain, Ronseal Walnut.

- Isopropyl alchohol.

- Antiqued cowhide thong, approximately 30m.

How many hours do you estimate you spent on the construction of this axe in total?

Including the design thought processes and the actual physical work, probably around 30-40hrs in total, although this was stretched out over a few months due to general life getting in the way; Matthew was very patient.

What was the most surprising part of the process for you?

I suppose that getting the head engraving pretty clean on the first attempts was pleasantly surprising, given that it was an all or nothing thing due to engraving directly through the gun blue-one slip and it would have been a start again scenario involving re-stripping and finishing before a second go. Phew!

Anything else you'd like to add?

I enjoyed this project very much, working together with Matthew was a great pleasure and his encouragement welcome. It is nice to have someone know, or at least have a strong vision of what it is they’re looking for in the design and execution of the piece. I do feel that my personal craft has been elevated during the project, with the head engraving and designs particularly. This axe is a large and heavy, a real beast of a weapon which took some careful hefting around during the process and that in itself was a learning curve for me. I would like to think that Matthew and I can collaborate again at some point; my techniques are developing and I would love for him to drop in along the way and share that journey again in the future.

====

The pleasure was all mine and I got a wonderfully crafted axe out of the project! And what a weapon it is –

beauty and the beast!

Further reading:

Mammen axe

https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/the-grave-from-mammen/an-axe-with-double-meaning/

Hurstwic Viking Age Arms and Armor: Viking Axe

http://www.hurstwic.org/history/articles/manufacturing/text/viking_axe.htm?fbclid=IwAR27PEg9_vS5pRnPoRIOqxTxxkau8q7LtEwBeXn2NLwusZnqAD9xv0kdSaM